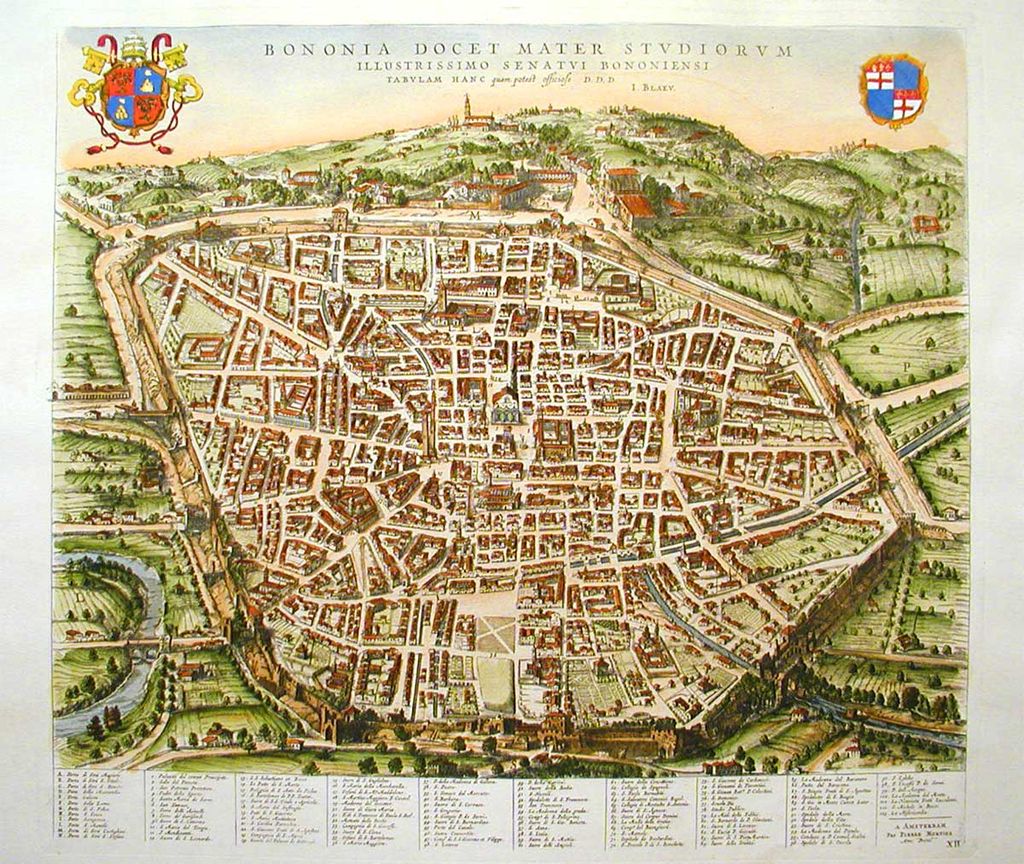

Bologna has had many sets of walls over the centuries, reflecting the changing environment and the growth of the city. The remains of three sets of walls shown on the map below are still visible to varying degrees.

The first set of walls

The first set of city walls is thought to be that of the Etruscans ( see my post The Etruscans and Bologna), but nothing visible survives either of it or of any later Roman wall.

With the slow disintegration of the Roman Empire, commerce and agriculture started to break down. There were many protracted wars, as various Germanic tribes invaded northern Italy and the Byzantines tried to retain what they could of the empire. The need for city walls was imperative.

The first visible remains of a set of walls belong to one built to meet this need. Its date of construction is not known but is somewhere between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was probably based in part on the Roman wall but enclosed a significantly smaller area, as Bologna was much smaller in those difficult centuries than it had been in Roman times.

This set of walls is shown in blue on the map above. There was thought to have been an extension to these walls to enclose the area occupied by the Lombards after their conquest of the city in the 8th century and it would have included the location described in a previous post, Santo Stefano – Bologna’s Mystical Past.

The wall was made of a local dark coloured stone called selenite, which has visible flecks of light coloured gypsum. Whilst more of this wall probably survives, incorporated in the walls of the jumble of medieval buildings in central Bologna, one small portion is visible today in a courtyard off Via Manzoni, near Via Galliera. A larger section can be seen inside the nearby Medieval Museum, also in Via Manzoni.

Some order returned to Italy in the tenth century under the rule of the German emperors. However wars continued. For example, Bologna joined the Lombard League in a series of conflicts resisting the power of the emperor Frederic Barbarossa. Nevertheless, increasing commerce and agriculture led to a growth of population and of the wealth of the cities of northern Italy. In addition, Bologna’s University was founded in 1088 ( see my post Bologna’s Elevated Medieval Tombs), and many students came to live in the city.

The second set of walls

For Bologna, all this meant that a new set of walls to encircle the much larger city was needed. The common name given to these walls is the “Cerchia del Mille” or ‘Ring of the Millennium” as it was thought to have been constructed around the year 1000, although the date is uncertain and probably a century later. It’s shown in green on the map.

These walls had 18 gates, although only 4 have survived. They’re called ‘torresotti’ as each one comprised a gate under a tower. The photo below shows the San Vitale gate. In the shop next to the gate is one of the few sections of these walls still visible.

Another remaining gate of this second set of walls is Porta Govese. The apartment in the tower would be a great place to stay!

A section of the second set of walls in Piazza Verdi was uncovered early in the 20th century and forms part of the back wall of the San Giacomo Maggiore complex.

Bologna became a major centre of manufacture and trade driving continued growth and a temporary wall of wood had to be constructed in 1226 to protect new parts of the city. This was a period of ongoing conflict between Italian city states, associated with the struggle for power between the Emperors and Popes. Bologna was involved in various wars.

The third set of walls

A third set of walls was built over many years, replacing the wooden palisade. The brick structure was built between 1327 and 1390. It extended for 7.6 km, compared to just 3.5 km for the previous walls, had 12 gates, and was surrounded by a ditch system. The line of these walls appears in red on the map at the top of this post.

There is a theory that each of the 12 gates represented one of the 12 signs of the Zodiac, supported perhaps by the fact that the University at that time included Astrology in the curriculum of the medical school. This was the genesis of astronomical studies. Copernicus may have studied astrology during his time at the University. He later wrote a book proposing that the planets rotate around the sun. For a further astronomical link to the city, see another post in this blog, The Meridian Line of San Petronio.

Early in the 20th century it was decided to completely demolish the third set of walls as part of a modernisation program, similarly to what had been done in Paris by Baron Hausmann. Also there was considerable unemployment at the time and the demolition was seen as a job creation scheme.

Most of the walls were demolished and only a few short sections remain. Originally it was intended to demolish all the gates as well, but their historic value was recognised, and all but 2 survived.

Surviving gates

There are 10 surviving gates, all shown on the map at the start of this post.

Anyone arriving by train can’t miss the imposing Porta Galliera which was remodelled in the 17th century when Bologna was a part of the Papal States.

Porta Maggiore was being demolished when the original medieval gate was discovered underneath its 17th century additions and it was saved. As such, it’s probably the most original in appearance of the 10 remaining gates of this third set of walls.

Porta Saragozza underwent heavy rebuilding in the 19th century, probably related to the fact that it leads to the Sanctuary of San Luca. The procession that starts from here was described in a previous post, The Descent of the Madonna of San Luca

At Porta San Felice, tiny sections of the wall remain attached to the gate.

The original Porto Santo Stefano was demolished in the 1840s and a customs post was built. At this time, Bologna was still in the Papal States as Italian reunification had not commenced. A World War Two era sign in German “nach Florenz” or ” to Florence” printed on a wall is slowly fading from view.

Surviving sections of wall

Some sections of wall survive and are marked on the map above as thick red lines. The longest stretches for around 470 metres (approximately 520 yards) at the northeast of the city, around the intersection of Viale Pichat and Viale Filopant.

Some remnants are quite small.

Some stretches have survived as they are incorporated into building structures. Most significant are the twelve churches dedicated to the Madonna that were built along the walls to protect the city.

Other vestiges of the wall incorporated into buildings can be spotted around Bologna .

Curiosities

As well as roads, canals also entered the city. Bologna in the middle ages was an industrial centre producing amongst other things, silk cloth. This required flowing water to power mills. For security, these entrances were able to be closed off using iron gates. One of these remains where the Aposa canal enters the city.

For more on Bologna’s canals, see another post in this blog, A Walk along Bologna’s Navile.

Above the stream at this point is the church of Santa Maria della Grada or Saint Mary of the Grate. It contains most of the body of Saint Valentine, now famous through modern marketing activity surrounding his day in February. His head was taken to Rome in the 16th century.

Along Viale Panzacchi, a section of a fort that formed part of the wall defences has been incorporated into an apartment building and the crenellations can still be seen.

In the 15th century, Bologna’s government was unstable, with powerful families vying for control. In 1443 Annibale Bentivoglio wrested control of the city from the Canetoli family.

Two years later, as a peace-making gesture, Annibale was invited by Francesco Ghisliera, a friend of the Canetoli, to a christening. It was a trap, and a waiting gang stabbed Annibale to death on his way home. His supporters won a subsequent battle with those of the Canetoli at a small gate to the city known as the Pusterla del Pratello. As a symbolic act, they bricked up the gate, which is still visible today in Viale Giovanni Vicini. This remaining section of the wall also forms part of the structure of the church of San Rocco.

Bologna’s walls would have made an extremely impressive site but fortunately there is enough remaining to enable us to imagine what they would have looked like in their entirety.

A number of Italian towns do retain their complete walls. Amongst those not too far from Bologna which are worthy of a visit are Ferrara, Lucca, Marostica, Treviso and Montagnana.

Torresotto di Porta Nova, marked A on the map, during a Festival. (P. Granville)

You can watch my short Relive video of a walk around the walls here.

© P. Granville 2017-2024