A Bologna museum not well known to visitors is the house of Giosuè Carducci. The museum has two parts. The ground floor is home to the Museo Civico del Risorgimento or Civic Museum of Italian Reunification, whilst on the first floor you’ll find preserved rooms of the home of the great Italian poet Giosuè Carducci.

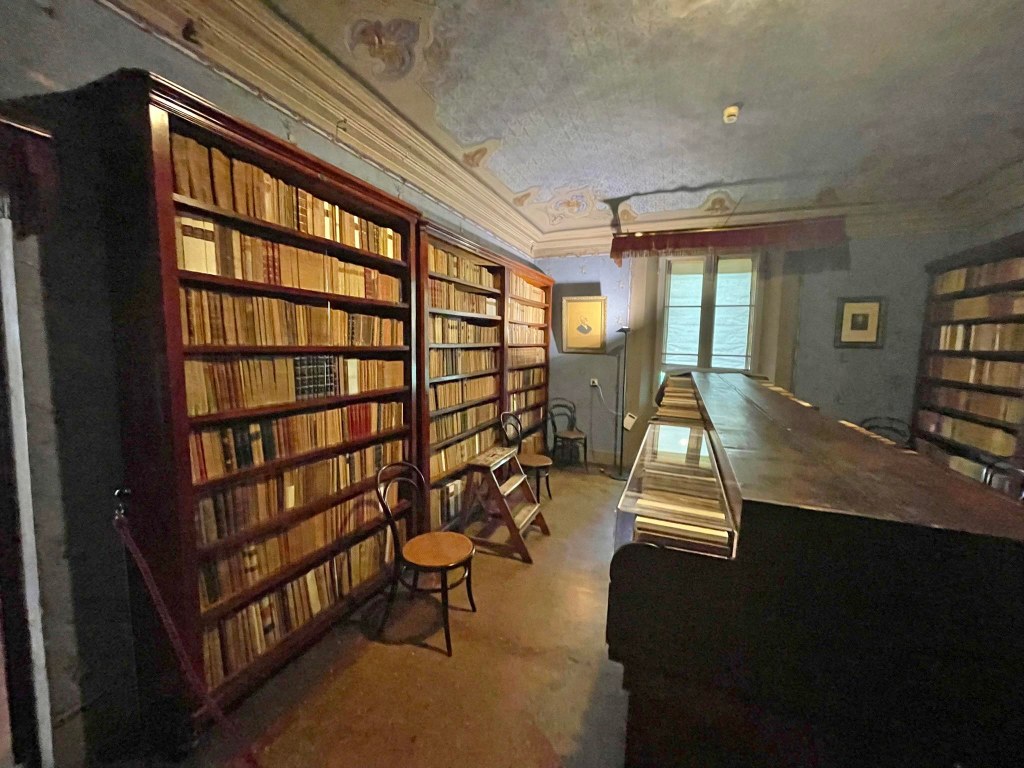

A church and oratory were built on the site in the early 18th century for the Confraternity of Santa Maria della Pietà after a fire destroyed their previous buildings. In the 1800s, it was converted into a residence and renovated by various owners. Carducci began renting the building in 1890 when his previous home became too small for his growing collection of books. Built onto the city walls (see my post The Walls of Bologna ), at the time it was quite isolated and almost in the countryside.

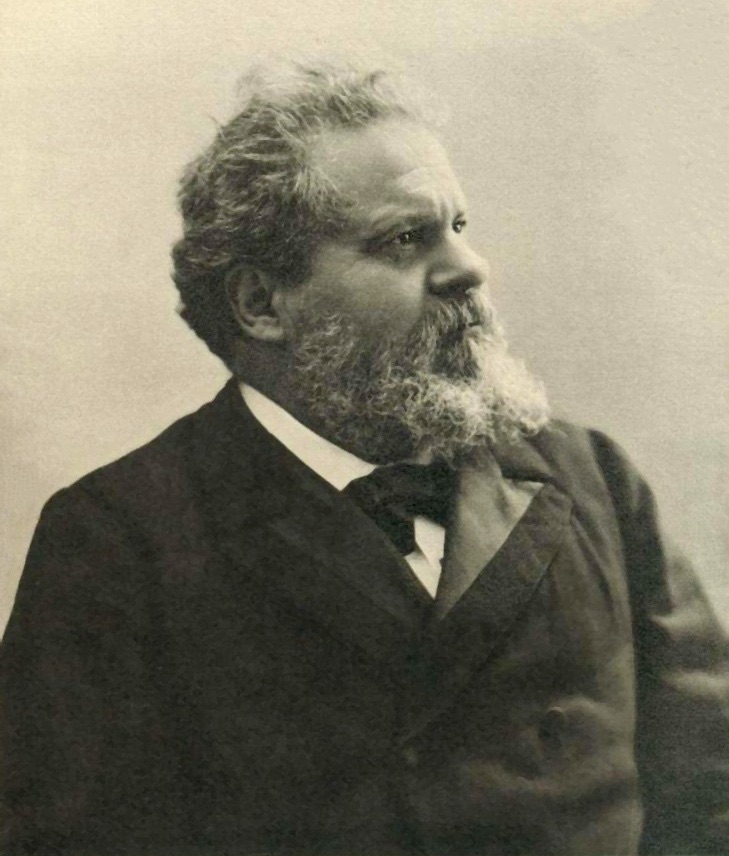

Giosuè Carducci

Giosuè Carducci was a highly influential 19th-century Italian poet as well as a writer, literary critic and teacher. He was born in Tuscany in 1835 and was writing poetry by the time he was 10 years old. After receiving a scholarship, he attended the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, a prestigious university. Carducci was one of a group of young poets wanting to abandon romanticism and to return to classical models.

After graduating, Carducci gave private lessons, as he was unable to find work as a school teacher due to his political beliefs as well as those of his father. Giosuè was strongly anti-clerical and a republican at a time when Tuscany was still a Grand Duchy ruled by the House of Lorraine. After Tuscany became part of the new unified Italy in 1860, the situation improved.

In 1860, Carducci became Professor of ‘Italian Eloquence’, or literature, at Bologna University. He was to remain in Bologna for the rest of his life.

A notable work was his 1863 poem “Inno a Satana” or “Hymn to Satan” in which Satan represents reason, freedom, and progress. At the time, Bologna was still ruled from the Vatican as part of the Papal States, and the poem was a challenge to that situation.

Tu spiri, O Satana,

Nel verso mio

Se dal sen rompeni

Sfidando il dio

De’ rei pontefici

De’ rei cruenti;

E come fulmine

Scuoti le menti.

You breathe, O Satan,

in my verses

when from my heart explodes

a challenge to the god

Of wicked pontiffs

bloody kings;

and like lightning you

shock men’s minds.

Carducci reached his creative peak in the 1880s. In later years, he became more religious, and his republican ideals weakened. His bedroom, like other rooms unchanged from when he lived in the house, has a copy of Raffaello’s Madonna della Seggiola hanging from the wall.

As well as poetry, Carducci wrote some 20 volumes of literary criticism, biographies, speeches and essays and translated the poetry of Heine and Goethe from German to Italian.

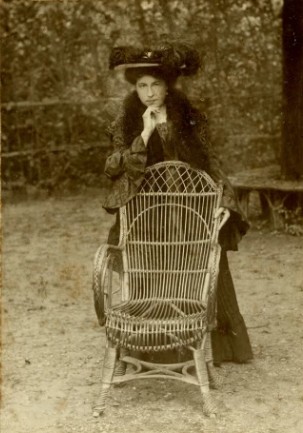

The women in Carducci’s life

In 1859 Carducci had married Elvira Menicucci with whom he had 5 children. However, he is said to have had over 30 lovers. After 13 years of marriage, he began a relationship with Carolina Cristofori Piva that lasted until her death 10 years later. Carducci’s poem Alla stazione in una mattina d’autunno, “At the station on an autumn morning” describes a woman named Lidia parting from a railway station. This is generally thought to be based on Carducci farewelling Carolina when she was leaving Bologna.

O viso dolce di pallor roseo,

o stellanti occhi di pace, o candida

tra’ floridi ricci inchinata

pura fronte con atto soave!

O sweet face of pale rose,

o starlit placid eyes, o snow-white

forehead ringed with luxuriant curls

gently bending in a nod of love.

His wife, Elvira, is recorded as having said to some of her friends “Come se qua a Bologna non ci fossero abbastanza puttane. Uno di questi giorni, però, se mi gira le faccio la posta e metto le carte in tavola” – “As if there weren’t enough whores here in Bologna. One of these days, though, if I feel like it, I’ll lie in wait for her and lay my cards on the table.”

Other women in Carducci’s life included Dafne Gargiolli, Adele Bergamini, Silvia Pasolini, and the English-born Italian writer Annie Vivanti.

Carducci was also very fond of food and wine. His favourite tipple was an Italian gin Gineprina d’Olanda Imea.

Carducci’s health deteriorated over the last 22 years of his life, and in 1899 he suffered a stroke which left him with a paralysed hand and barely able to speak.

In 1906, Carducci became the first Italian to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Italy was unified as a constitutional monarchy in 1861, and in 1878, Umberto I became King and his wife and cousin Margherita of Savoia became Queen. She had performed an important unifying role in the new kingdom for many years as her mother-in-law, the former queen, had died in 1855.

Margherita was a great admirer of Carducci, who in 1878 had written an ode in her honour on the occasion of a royal visit to Bologna. She had proposed awarding him the Savoy Cross of Merit, which Carducci refused.

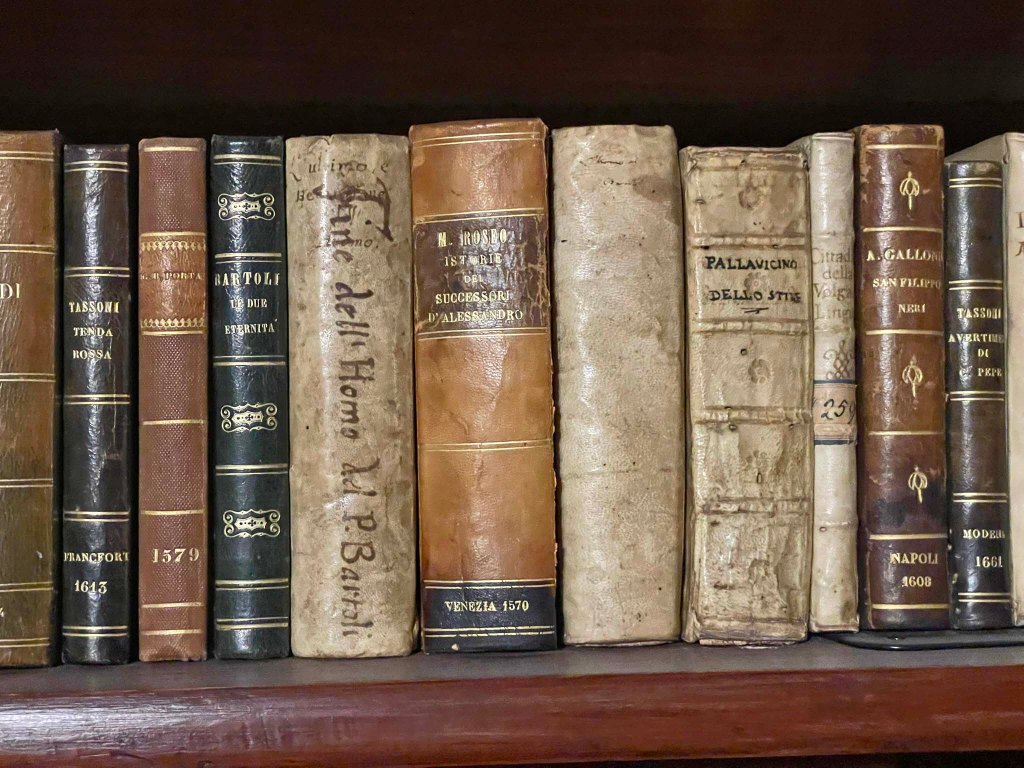

Towards the end of his life, the seriously ill and financially strapped Carducci became concerned about the future of his library. In 1902, Margherita, by then the Queen Mother, purchased the library. In 1906, she acquired not only the house, so that the library could remain there, but also the surrounding land.

Carducci died in 1907, and Margherita donated all to the Comune, or City Council, of Bologna. In 1921 the museum house was inaugurated, with Margherita in attendance.

The Museum of Reunification

The ground floor, which was occupied at various times by Carducci’s daughters and their families, is now home to a museum that examines Italian reunification from the time of Napoleon until the end of World War I, with an emphasis on Bologna. Over this time, Italy went from being divided into numerous small states to a kingdom covering slightly more territory than it has today. Some was lost after World War 2.

The museum was founded in 1893 and has been in the current location since 1990. It contains memorabilia, uniforms, weapons, paintings and documents.

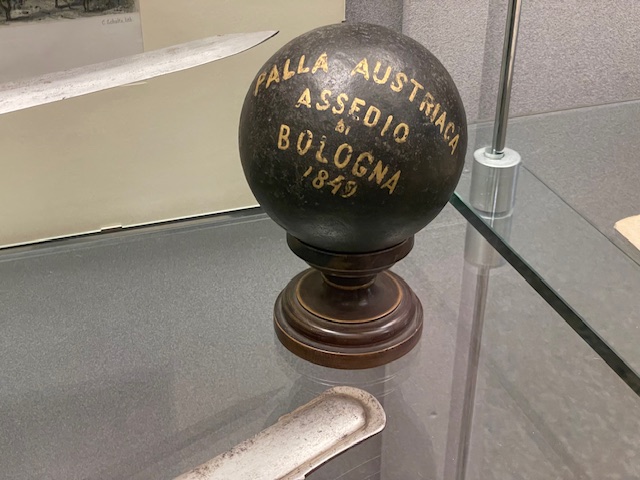

In November of 1848, Romans rose up against the oppressive rule of the Church and formed a republic. The Pope fled to the fortress of Gaeta across the border in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Other cities in the Papal States, including Bologna, joined the republic. The Pope called for assistance and Austrian forces besieged Bologna in May, 1849. The city surrendered after a prolonged and intensive bombardment.

In 1848, the city had asked residents to donate valuable items to support the war then underway between Piemonte and the Austrians. On display is a donated earring of low value that demonstrates the wide support for the cause.

After the Austrians captured Bologna, they executed the Bolognese priest Ugo Bassi, who had acted as chaplain and medical orderly in Garibaldi’s forces. He had been captured following a retreat of Garibaldi and his troops after unsuccessful battles with French soldiers sent to Rome to restore the Pope’s rule. There is a street and a statue of Bassi in central Bologna (see my post Bologna’s Public Statues.)

In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi led his volunteer army to conquer the vastly larger forces of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which was then the largest of the Italian states. This led to the creation of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

At the rear, there are two cabinets containing the stamp and postal history collection of Professor Giorgio Tabarroni, which was donated to the museum a few years after his death in 2002. The collection includes stamps, postcards, envelopes and letters.

Details about visiting the museum can be found at this site. A visit to the Carducci apartment upstairs is included in the modest ticket price but must be accompanied by a guide. At the time of writing this blog, tour times were listed here.

© P. Granville 2026

Leave a comment